Higher Calling

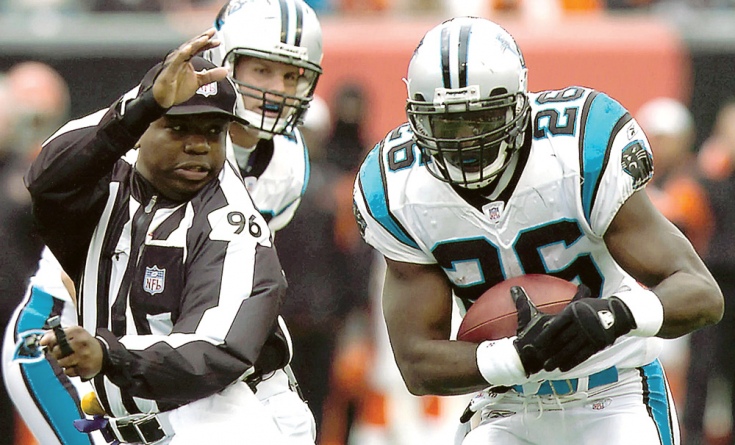

As referees in the NFL and NBA, alumni Undrey Wash and Monty McCutchen hold two of the most exclusive and highly scrutinized jobs in the world. UT Arlington served as training ground for both.

A dozen large and angry men surrounded Undrey Wash on Super Bowl Sunday last February. They cussed, they pushed, they shoved. Wash, on all fours, head extended, pushed back as the melee engulfed him. But he wasn’t there to fight; his job was to determine the winner.

If you were among the 106.5 million TV viewers of Super Bowl XLIV, you remember the play. The ultimately victorious New Orleans Saints began the second half with an onside kick, resulting in a mad scramble for the football. The 1986 UT Arlington graduate has often stuck his nose in the middle of such free-for-alls during his 10 years as a National Football League official. But the stakes were never this high.

Five months later, fellow alumnus Monty McCutchen played a similar role on pro basketball’s biggest stage. He headed the three-man crew that officiated Game 2 of the National Basketball Association Finals between the Los Angeles Lakers and Boston Celtics. Hollywood A-listers Jack Nicholson, Steven Spielberg, and Leonardo DiCaprio were among the 19,000 who packed the Staples Center for the biggest show in town. Another 15 million watched on TV.

Unlike pro football officials, who remain largely anonymous, NBA referees are widely recognized—and critiqued. Boos cascaded every time McCutchen (’88) called a foul on Lakers star Kobe Bryant. Through dark sunglasses, Nicholson glared at the 17-year NBA official. Even when McCutchen is right, which is most of the time, half the people won’t admit it. Fans, players, and coaches just want their team to win, and their passion sometimes turns venomous.

McCutchen and Wash say that’s part of the package when you ascend to the highest level of this elite occupation.

A STAR IN STRIPES

Close Calls

Undrey Wash compares being an umpire in the National Football League to “crossing a freeway during rush hour.”

Wash’s road to the top began on the UT Arlington intramural fields. While pursuing his systems analysis degree, he earned $5 a game officiating various sports. His first taste of on-field animosity came in 1982 during a fraternity softball game. He called a runner out at second base, and the player began to argue.

“I could handle that. I had pretty thick skin. Then, all of a sudden, his girlfriend started to chime in on me,” Wash says with a laugh. “That’s when I lost it.”

He decided to focus on football and moved quickly through the ranks: peewee, junior high, sub-varsity, varsity, small college. He worked in the Southwest Conference for a year before it dissolved, then moved to the Big 12. After a year in the instant replay booth, he officiated his first NFL game in 2000. At age 38 he was the second youngest official in the league.

NFL crews have seven members. Wash’s position is umpire, which until this season placed him in the middle of the defense. The umpire’s primary task is controlling the action between the offensive and defensive linemen. To survive, he learned to dodge 300-pound bodies intent on flattening everyone in their path.

“It was like crossing a freeway during rush hour,” Wash says. “And it was only getting worse.” That’s why the NFL moved umpires behind the offensive backfield this season, out of the line of fire.

Even that vantage point wouldn’t have kept him from missing most of the 2007 season after rupturing the patellar tendon in his left knee when a player celebrating a touchdown was pushed into him. That’s the only thing that has slowed Wash’s rise.

After working the playoffs and a couple of championship games, he knew he was among the league’s top-rated umpires. They’re graded on every play of every game, and only those who rank the highest advance to the postseason. But was he good enough for the world’s grandest sporting event?

“You never know,” he says, “until you get that phone call.”

Mike Perreira, then director of NFL officiating operations, delivered the good news at the desk of Wash’s Las Colinas Allstate office, where he’s a claims controller on weekdays. As Wash thought about his injury, the birth of his daughter, and all the people who helped him along the way, tears welled.

“It was an emotional moment,” he says. “As soon as you hang up the phone, you’re going, ‘Yeah!’ ”

As for the Super Bowl itself, Wash describes it as business as usual except for the thousands of camera flashes at the opening kickoff. And the onside kick. Before the game, the Saints’ special teams coach told him the surprise move was in their game plan, but Wash didn’t know when.

“I tried to put my hand in the pile and feel the ball,” he said. “It was a feeding frenzy and definitely survival of the fittest.”

Wash estimates that football officials have less than a 1 percent chance of landing a spot on one of the NFL’s 17 crews. Most who do never sniff the Super Bowl. Carl Cheffers, Wash’s friend and crew chief last season, knows how rare an accomplishment it is.

“Think about the thousands of officials who want to make it to the NFL. To be selected and have success is a great achievement in itself,” Cheffers says. “You can’t get any higher validation of your work than to get to the NFL and work the Super Bowl. Undrey is among the very, very few to accomplish that feat.”

FROM INTRAMURALS TO THE NBA

Conflict Resolution

National Basketball Association referee Monty McCutchen says dealing with disgruntled players is just part of the job.

The NBA officiating fraternity is even more exclusive. Only 58 others share McCutchen’s profession. It’s a full-time job, unlike in the NFL, and the travel is tougher than being a New Jersey Nets fan. During the November-April regular season, McCutchen is on the road 24–26 days a month.

“Being away from my wife and children is the hardest part of the job,” he says from his home in Ashville, N.C. “When you’re in 14 cities in a month, that’s very stressful on family life.”

McCutchen first put a whistle in his mouth working junior college intramurals. By the time he hit the

UT Arlington intramural courts, he had officiated junior high, freshman, and junior varsity games.

“The first time I blew my whistle, I didn’t raise my hand or do anything,” he recalls with a laugh. “Thankfully, the kid I was trying to call a foul on raised his hand, or I might still be standing there today.”

As a 21-year-old junior, McCutchen quickly became the referee every intramural team requested. But he wanted more, so he wrote the NBA. The league replied that most of its officials had 15–20 years experience and suggested he try the pro-am leagues.

With help from his dad, who borrowed money against a horse, McCutchen scraped together enough cash to travel to Los Angeles for a camp run by NBA referee Hugh Hollins. It was his first taste of life as a basketball official, and he was hooked. A week after graduating from UT Arlington with a degree in speech communication and English literature, he moved to L.A.

“I knew officiating was something I was going to pursue and pursue wholeheartedly,” he says.

He was invited to a national pro-am league and eventually landed a job in the Continental Basketball Association, which serves as a training ground for NBA hopefuls. It was during a CBA game in Pensacola, Fla., that a fan spouted: “McCutchen, you’re like 7-Up. Never had it, never will.” It still makes him laugh.

He was promoted to the NBA in 1993 at age 27 and, like Wash, was the second youngest referee in the league. He worked his first playoff game in 2000 and his first NBA Finals in 2009.

Now 44, McCutchen knows every NBA player (even those who never leave the bench), calls them by their first name, and expects the same respect in return. If he doesn’t get it, he says, he strives to remain approachable, firm, and above all, consistent. But with the world’s greatest athletes moving at breakneck speed, missed calls—and conflict—are inevitable.

“You must understand that you are going to fail,” says McCutchen, who also officiated Game 6 of the 2010 NBA Finals. “Hard work minimizes failure, but you can’t be defensive about every call or you won’t grow and gain the confidence of those you work with.”

He’s obviously respected by the league’s officiating supervisors, as well as the coaches and general managers. They’re the evaluation team that determines which referees advance through the playoffs. With two NBA Finals under his belt, McCutchen is in rare company.

“To reach the NBA Finals, Monty is considered one of the best,” says Duke Callahan, who worked Game 2 alongside his friend. “He puts the game first, the crew second, and himself third. That’s the sign of a great referee.”

McCutchen and Wash have never met, but they are kindred spirits. They know what it’s like to work at one of the hardest and least-appreciated jobs in sports. And they know how it feels to reach the top.

This is very cool, just goes to show how hard work and determination can get you far in this cynical world we live in. As a plus its also cool that we have Mavs in the world of professional sports.