Cities are growing—especially in North Texas. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington Metroplex grew by 19% between 2010 and 2019, the largest gain in the country. With more than 7.5 million people, DFW is the most populous metropolitan area in Texas and the fourth largest in the U.S. But with that kind of accelerated growth comes problems.

Historically, cities were built alongside sensitive watershed environments like the Trinity River due to the resources they provided, such as drinking water, food, and the transportation of goods. But as these areas grew, the effects of urban development on watersheds often weren’t taken into consideration, resulting in increases in serious environmental issues and negative social outcomes.

Researchers from The University of Texas at Arlington’s College of Architecture, Planning, and Public Affairs (CAPPA) and Department of Civil Engineering are working to develop solutions that could help DFW and other metroplexes continue their urban growth while protecting the surrounding environments.

“The DFW area is booming significantly and rapidly, and many different places are experiencing some issues due to this development,” says Nick Fang, associate professor of civil engineering. “When doing this kind of urban planning, people often have a tendency of overlooking the adverse impacts from the projected development, but we need to respect nature and the watershed.”

Exploring Urban Development

Try searching for “watershed urbanism” online and your inquiry will likely come up short—the concept is so new, it’s still being defined. Among those helping write this new history are Dr. Fang and Kevin Sloan, a landscape architect and professor of practice in CAPPA, who are bringing their varied individual expertise to inform and mold the emerging concept.

The general idea is that watersheds and metroplex regions are not isolated phenomena. One should not dominate the other—instead, urban planners should always take into consideration how the natural environment will be affected by development and vice versa. In doing so, we can greatly diminish the negative consequences that often emerge.

Though the idea may seem simplistic—even obvious—few development projects operate with this mindset.

“From the urban planning and architectural standpoint, they want to build something, but, before they do, they need to actually figure out how to respect what’s nature-given and what’s inside the watersheds,” Fang explains. “Then they can design, plan, and build with much better quality and without being worried about future issues caused by human actions today.”

“You want to build a systematic view of a watershed corridor for planning purposes, design purposes, flood management, and so forth,” Sloan adds. “This is a comprehensive design.”

Watershed urbanism is a topic that is showing great potential for ecology, for hydrology, and on and on. It’s going to save the world.

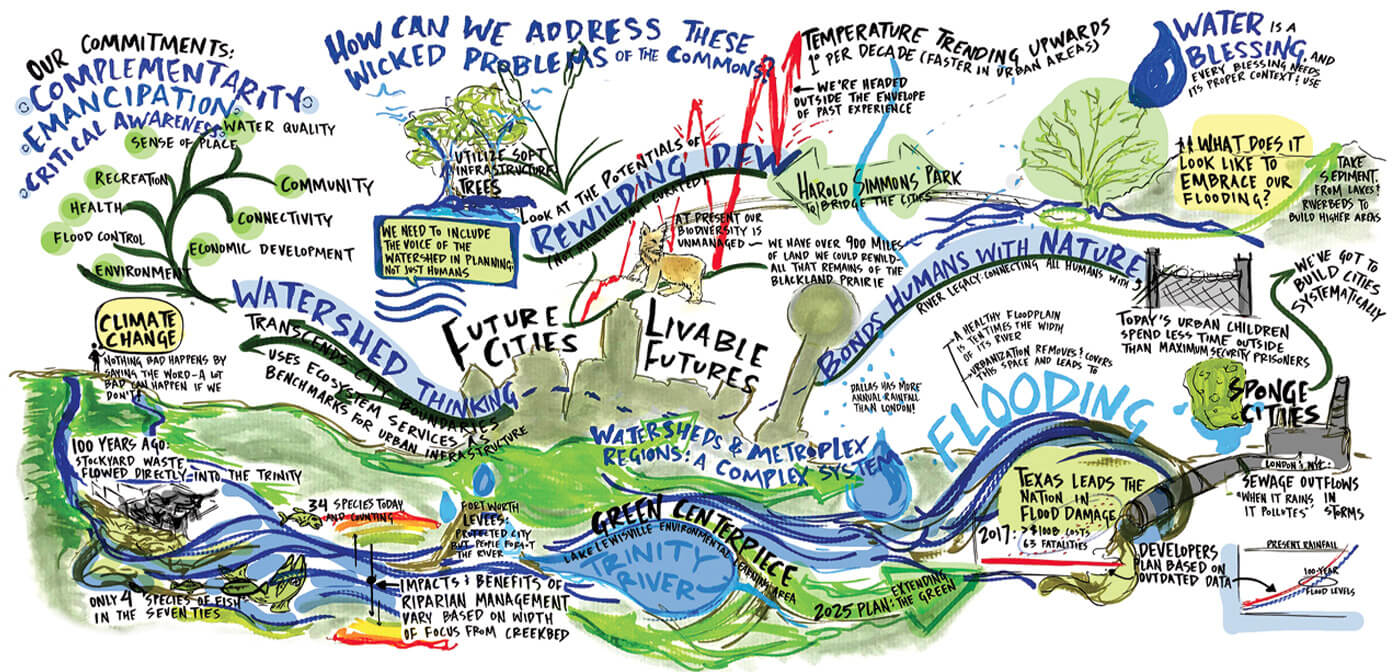

In 2019, the pair worked with Adrian Parr, former dean of CAPPA; Michael Zarestky, former civil engineering associate professor; and Meghna Tare, director of sustainability, to develop “Future Cities, Livable Futures: Watershed Urbanism,” a regionwide conference focused on watershed urbanism. Funded by a National Science Foundation grant, the event brought researchers together with entities across the private and public sectors to explore how this emerging concept could be applied to the Trinity River Watershed.

“We wanted to bring all of the different kinds of personnel and experts related to watersheds and urban planning together to get a discussion going,” Fang says. “The idea was, ‘Let’s have a discussion about what is going on in DFW and what is needed for the future.’”

Resilient Watershed Urbanism

Sloan is an expert on rewilding, a concept he describes as designing environments with a very specific calculation in mind for what you want the results to be.

“We’re talking about making the hydrology and ecology do the same kind of thing for itself that we make hydrology and ecology do for landscape architecture,” he explains. “It’s just remapping it all back together so it’s one cohesive phenomenon, not landscape over here, civil engineering over there.”

In 2019, CAPPA awarded funding for four interdisciplinary research grants focused on water and human settlements. Sloan and Fang are collaborating on one, “Assessing the Value of Resilient Watershed Urbanism,” that looks at riparian zones along riverbanks in DFW to investigate ways to use the watershed to accommodate both urban development and rewilded nature.

Illustration by Emily Jane Steinberg

Fang brings his expertise on hydrology and hydraulic modeling to the team. He has worked on several projects that address flooding in Texas, such as a recent grant from the Texas General Land Office analyzing drainage and proposing recommendations for future flood prevention in nine different southeastern counties.

“When we deal with urban planning, you have to think about how that can blend into the concept to find a common ground,” he says. “If you compromise a lot of features in the watershed or do not respect its nature, eventually you’re going to have flooding issues. But if you plan well, you can take advantage of the watershed system while still enjoying the amenity.”

Now that the researchers have begun to explore real-world applications for watershed urbanism, they have grown excited for its seemingly infinite potential.

“Watershed urbanism is a topic that is showing great promise for ecology, for hydrology, and on and on,” Sloan says. “It’s going to save the world.”

North of the Island

Directly north of downtown Fort Worth, an island is forming. Due to the city’s rapid population growth and development—both of which are projected to continue into the future—many Fort Worth neighborhoods are at risk of flooding from the Trinity River. An increase in impermeable surfaces like concrete and pavement means more rain is running into the river. The city’s 1960s levee system is overstressed.

The proposed solution is to cut a bypass channel that will result in the creation of Panther Island, a project that promises both flood mitigation and a new mixed-use waterfront community. Though it has a seemingly admirable goal, Dennis Chiessa, assistant professor in the School of Architecture, worries the project hasn’t taken into consideration how the development will affect all of its surroundings—and how it may actually create new problems.

Nick Fang believes urban developers should respect and utilize watersheds in their designs; Dennis Chiessa is studying the potential sociological consequences of a planned development in north Fort Worth; Karabi Bezboruah is collaborating with universities in India to develop solutions to urban flooding.

Instead of the effects of urban development on the surrounding natural environment, Chiessa’s concern is for the potential sociological consequences on the majority-Latino community that inhabits Fort Worth’s historic North Side neighborhood, located on the other side of the new channel. His research project is funded through one of CAPPA’s interdisciplinary grants and includes three other CAPPA faculty: Associate Professor Taner Özdil, Assistant Professor Rod Hissong, and Instructor Nazanin Ghaffari.

“We’re looking at the North Side of Fort Worth through the lens of development to understand how the existing community is impacted,” explains Chiessa, who grew up on the North Side. “There are obvious concerns about what will happen if 20,000 people come to live and work on Panther Island and what effect that’s going to have on the neighborhood, including gentrification and displacement, as well as potential benefits like jobs and increased tax revenues.”

The team and its student researchers have been exploring how different sites within the North Side could be transformed to positively reimagine the neighborhood’s future once the island is complete. They have shared these ideas with residents to motivate them to get actively involved in advocating for the benefit of their community, with the goal of increasing awareness of the issues surrounding the built environment.

“Understanding how water, the new canal, and development can work together is critical to ensuring this project benefits the larger public,” Chiessa says.

Mitigating Urban Flooding

Though their primary focus remains on the DFW Metroplex, some UT Arlington researchers are looking beyond its borders to apply their watershed urbanism research—way beyond. For public affairs and planning Associate Professor Karabi Bezboruah, civil engineering Professor Melanie Sattler, and engineering faculty Arpita Bhatt, the northeast Indian city of Guwahati offers a case study for the problems that can arise when urban development and environmental reality clash.

During monsoon season, the Brahmaputra River flowing through Guwahati regularly rises above its danger level, resulting in frequent flooding of the low-lying areas. The problem is exacerbated by additional factors like rapid population growth, construction in floodplains, deforestation, and a lack of integrated water management policies and effective infrastructure planning.

Drs. Bezboruah, Sattler, and Bhatt are collaborating with Cotton University and Shiv Nader University to identify grassroots strategies for avoiding and mitigating urban flooding’s socioeconomic and health impacts. The team will share the resulting water management policies and infrastructure planning practices via training workshops at Cotton University, with government officials, NGO executives, engineers, architects, and real estate developers being invited to attend.

“It’s a great opportunity to collaborate with eminent international researchers on the topic of urban flooding and to come up with solutions that will have significant social impact,” says Bezboruah.