Fighting Back

As bullying incidents become more widespread and vicious, UT Arlington professors are engaged in sweeping research and scholarly studies to curb the troubling trend.

· Summer 2012 · Comment ·

Jon Carmichael was 13 with bright blue eyes and sandy-blonde hair. He loved football, his horse named Handsome, and a stray dog he called Daisy. Small for his age, Jon was bullied relentlessly by classmates. Media reports detailed how fellow students called him names and flushed his head in toilets. One day at school, his parents say, he was stripped nude, tied up, and dumped in a trash can. Not long after that, in March 2010, the young teen hanged himself in a barn near his family’s home on the outskirts of Cleburne. Long an unfortunate staple of school yards, bullying has reached an epidemic, fueled in part by the Internet and social media. Bullies who once ruled the lunch room now take to Twitter and texting to torment their classmates, often cloaking themselves in anonymity and making it impossible for their targets to avoid the harassment.

“It is important to figure out the motives of the bullies to address and prevent the problem.”

Students like Jon Carmichael have turned to suicide to escape their tormenters. He isn’t alone. Asher Brown, a 13-year-old Houston boy, shot and killed himself after his parents say he was bullied at school for being gay. Tyler Clementi, an 18-year-old freshman at Rutgers University, jumped to his death from the George Washington Bridge after a romantic encounter with a man was secretly recorded and streamed online. Phoebe Prince, a 15-year-old girl in Massachusetts, hung herself in a stairwell after months of being bullied.

While suicide cases are extreme, experts agree that the bullying problem has become more acute than ever. “Bullying has been around for a long time,” says Alejandro del Carmen, chair of the Criminology and Criminal Justice Department, “but we are seeing higher levels of sophistication and aggression.”

From psychology and education to criminal justice and social work, UT Arlington professors are working to evaluate health problems of bullying victims, help schools craft better policies, determine why some kids bully, and advance our understanding of bullies in the workplace.

SICK OF THE ABUSE

Estimates of the extent of bullying range widely. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, about 28 percent of students ages 12 to 18 said they were bullied in 2009, the last year for which NCES figures are available.

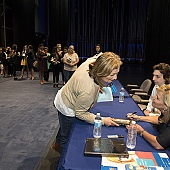

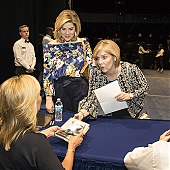

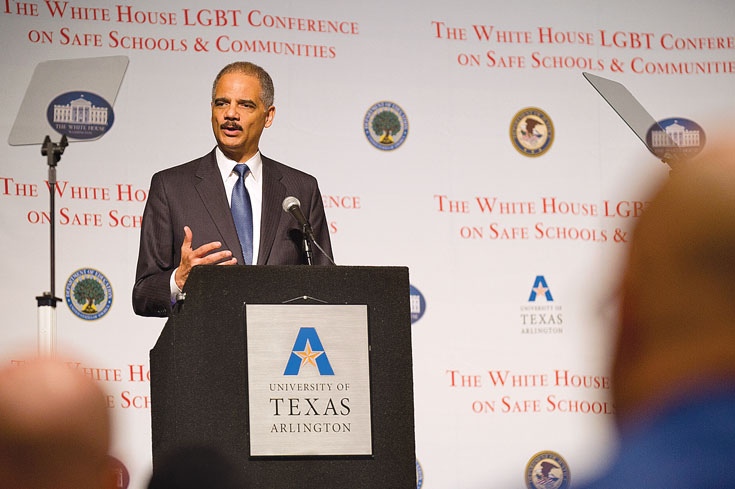

Parents are asking schools and communities to address bullying, and UT Arlington has responded. In March the University partnered with the White House to host a conference on bullying prevention and the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community. The event, one in a series coordinated by the Obama administration, featured impassioned remarks from Attorney General Eric Holder and Valerie Jarrett, senior adviser to President Obama.

HELP AND HOPE

Psychology Associate Professor Lauri Jensen-Campbell is exploring whether bullying leads to a decline in physical health, causing students to miss school.

Every day in the United States, 160,000 children miss school out of fear of attack or intimidation, the National Education Association reports. Psychology Associate Professor Lauri Jensen-Campbell is exploring whether these students also miss school because their physical health has declined.

“We know chronic stress can lead to real and serious health problems,” she says. “We wondered if bullying affected their immune system, leaving them more susceptible to colds and flus, and even affected their long-term health.”

Dr. Jensen-Campbell and a team of researchers interviewed about 300 students, mostly 6th to 8th graders who attend public and private schools in Arlington, and determined roughly one-third were victims of bullying, which they defined as repeated aggressive behavior. Using saliva samples, the researchers monitored the students’ cortisol levels.

In healthy children, cortisol peaks about 30 minutes after waking and falls throughout the day. Bullied children, on the other hand, showed flattened cortisol awakening response, which is associated with poorer health outcomes. This blunted awakening response could make children less able to handle threats to their immune system, resulting in more health problems. Children who are bullied show the same cortisol awakening response as someone who is suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, Jensen-Campbell says.

To determine whether health continues to suffer, Jensen-Campbell plans to revisit the students, most now in high school, this year to determine whether cortisol levels remained abnormal for the children who were bullied in junior high. She also is launching a project studying the hippocampus—the part of the brain that plays a crucial role in memory—of college students who were bullied.

“A lot of people will hear about bullying and say this is just kids being kids. This research tells us that it is not true,” she says. “Bullying is a very serious problem with very serious health effects.”

“It is important to figure out the motives of the bullies to address and prevent the problem.”

ZERO TOLERANCE

As a clinical psychologist, Jon Leffingwell has seen the emotional toll bullying can take. Children become depressed, withdrawn, angry, helpless, and, in extreme cases, suicidal.

Dr. Leffingwell, an associate professor of education, instructs teachers how to prevent bullying in the classroom. Formerly a consultant for school districts on the subject, he notes that research shows bullying intensifies when the economy struggles, which may have helped catapult the issue into the national spotlight.

Education faculty members Jon Leffingwell and Mary Lynn Crow, both clinical psychologists, advise bullied children to stop blaming themselves.

“There’s more anger, more frustration,” he says. “More kids might have trouble at home due to myriad problems, and they take that out on other kids. The weak tend to pick on the weaker.” Bullying spans all socioeconomic classes and races, adds education Professor Mary Lynn Crow, a clinical psychologist who counsels bullied children and their parents, as well as bullies themselves. Those most likely to be bullied include children with disabilities, children who are gay or lesbian or perceived to be, children who are passive or have few friends, children who are small for their age, or children who are just different.

Bullies frequently come from families or neighborhoods where violence is common, Dr. Crow says, and some have been bullied by peers or adults. Bullying does not occur in isolation, and prevention increasingly focuses on urging bystanders to stand up for victims.

Leffingwell and Crow advise bullied children to stop blaming themselves and to talk to someone. Out of embarrassment, many children keep the bullying a secret, which often makes it worse. Leffingwell urges school administrators to set a strict policy that prohibits bullying and encourages teachers to implement the rule in their own classrooms.

He believes schools should be proactive, offering lessons in conflict resolution and problem solving as early as grade school. Bullying is a learned behavior, which means bullies have the ability to change.

“Teachers and administrators have to say upfront that they will not tolerate this sort of behavior,” Leffingwell says. “Bullying is minimized when everybody in the school works together, and it needs to start at the top.”

“A lot of people will hear about bullying and say this is just kids being kids. This research tells us that this is not true.”

INSIDE THE BULLY’S MIND

Why do some children bully? Low self-esteem? Anger? Frustration? Abuse?

A team of criminal justice professors wants to tap into the mindset of the bully. Working with community groups, the professors plan to identify bullies of both sexes who attend schools in North Texas. The professors will survey the bullies to determine what fuels their behavior. The department conducted a similar study on why teenagers join gangs.

“A lot of research focuses on the victims of bullying, but we know little about what drives the bully,” Dr. del Carmen says. “It is important to figure out the motives of the bullies to address and prevent the problem.”

Schools and communities could use the data to design anti-bullying programs, provide counseling, and identify students who are at risk of becoming bullies. As teenagers across the country are being prosecuted for bullying, the issue has captured the attention of the criminal justice world.

“We criminologists are being challenged to step up and find ways to prevent these acts of bullying, which endanger our communities,” del Carmen says.

Adolescents aren’t the only targets.

A growing number of researchers are studying the phenomenon of adulthood bullying, which can include tactics such as verbal abuse and threatening conduct. About 35 percent of employees in the United States report being bullied at work, according to the Workplace Bullying Institute.

NATIONAL SPOTLIGHT

UT Arlington partnered with the White House to host a conference on bullying prevention in March. Featuring remarks by Attorney General Eric Holder, the event was one in a series coordinated by the Obama administration.

Social work Professor Ski Hunter is leading a project to determine how rampant workplace bullying is in higher education. She and colleagues are surveying social work departments at universities across the country. Dr. Hunter became interested in the topic after encountering a workplace bully.

“Bullies create a hostile work environment and are very damaging to workplace morale,” she says. “They choose their targets and harass, intimidate, and humiliate.”

Unlike school-aged bullies who often victimize classmates for being unusual or different, workplace bullies pick on the intelligent and well-liked, those who are good at their jobs. “They want to bring people down,” Hunter says. “They are driven by jealousy.”

The data that Hunter and her colleagues collect will help employers, just beginning to recognize the problem, to develop policies to deal with bullies.

“The bully flaunts power and authority, belittles and hurts people. The targets experience real and long-lasting effects. The problem can no longer be ignored.”

Hunter and fellow UT Arlington professors are making sure it won’t be.