Reclamation Tour Provides an Opportunity for CAPPA to Redesign Historic Black Settlements

Texas historic Black neighborhoods face significant issues, and we want to help.

Historic Black settlements in urban areas across the United States are being subjected to environmental and industrial hazards that jeopardize their health and survival. Reclaiming Black Settlement is a project that will bring together faculty and students from architecture, landscape architecture, and historic preservationist to create a design Playbook tailored to the needs of historic Black settlements in Dallas-Fort Worth, which are threatened by top-down development as a result of the City's explosive growth and sprawl. This is an extension of the Master of Landscape Architecture studio, LARC 5660, ARCH 5670 course. The Trinity River and the historic black towns of Joppa, The Bottom, Mosier Valley, and Garden Eden, Elm Thicket are the focus of the excursion. The studio course teaches how to conduct an in-depth inventory and analysis while keeping the original settlers in mind.

Apart from funding needed to revive these historic communities, it also requires people to admit their lack of understanding of these places is limited or superficial. People who are familiar with them can reveal their intricacies, mysteries, and challenges.

Dr. Diane Jones Allen, professor of landscape architecture, Dr. Kate Holliday, architecture historian, and Dr. Austin Allen, associate professor of practice in architecture, are facilitating this project and tour of the Freedmen's Towns. The SOM Foundation awarded the team a $40,000 grant to construct maps of freedmen's towns along the Trinity River and develop design guidelines for these Black Settlements.

The trip through the Dallas Freedmen Towns is another crucial step in this project, which will provide information in a case study for Joppa. In addition, it was an opportunity to show the students what they'll be working on and a run-through of the history and issues these communities confront.

The design Playbook will serve as a toolkit for other Texas communities experiencing similar difficulties. "These cities and towns no longer exist as communities; they are more historical sites because they've succumbed to the pressures. The goal is to put together a design playbook for Joppa and other towns that have started facing environmental pressures and environmental Justice issues, divided by the railroad tracks, communal pressures, zoning issues, development pressures, policy changes, and gentrification." Dr. Diane Allen stated.

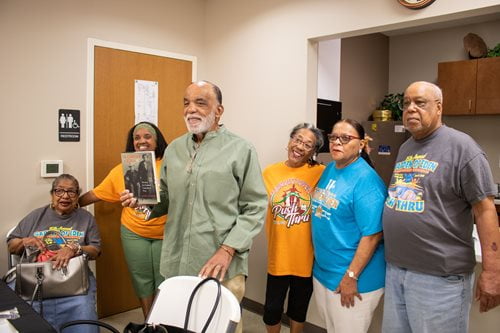

At the commencement of the tour, representatives from UTA Press and the Star Telegram were present, and the account of the tour is posted on the News website. The Fort Worth Star-Telegram is a daily newspaper in Fort Worth, Texas that serves Tarrant County and the western half of the North Texas metroplex, and since this project focuses on historically Black communities in Fort Worth and Dallas, having this piece showcased in front of such a broad audience was a tremendous opportunity.

A Journey Through the Freedmen's Towns

The tour started at the University of Texas at Arlington's Fort Worth campus, and just a short walk from the campus was the railroad tracks. There was a dividing line between white and black in downtown Fort Worth from the 19th century to the middle of the 20th century. Between the 1930s and 1960s, the urban renewal initiatives and additional railroad tracks in Fort Worth destroyed entire communities.

The "Historic Wall," a public art project at Central Station by the Trinity Metro, pays respect to the Black communities. The five-paneled wall, erected in 2002, commemorates the Black industrial and historic warehouse neighborhood. Dr. Holliday explain to the group what the depictions on the wall represents. The artwork was created to honor Black Fort Worth and its rich past, which had all but vanished.

The Garden of Eden

First stop, The Garden of Eden, a historically Black neighborhood in Fort Worth Texas, which was established around 1860 by freed slaves from Kentucky and Tennessee. Along the Trinity River, the settlement had a total of 54 households. The town now has 20 people, all of whom are descendants of the first settlers. One of the original descendants of the settlement, Delbert Sanders shared a brief history of the district and the challenges they are currently experiencing as he welcomed the group into his compound. He was born and raised in the neighborhood, and his family lived here for over 100 years.

The community had suffered through hard times until the neighborhood association was developed in 2004. Since then, the area is now designated a historic neighborhood. The Garden used to be a thriving settlement with schools, community centers, agriculture, etc. Factory and recycling enterprises have taken over the town, making the area less desirable. The roads are narrow and very close to house dwellings. On any given day, trailers and trucks pass by, with hefty loads and an excruciating noise coming from the vehicles Mr. Sanders stated.

After a brief chat with Delbert Sanders, the tour continued to the Valley Baptist Church to meet the rest of Sanders' family. They had resided in the area for generations and intended to establish a museum at the Valley Baptist Church to preserve the community's rich history. Drew Sanders' book, titled "The Garden of Eden: The Story of a Freedmen's Community in Texas," was published in 2015, and it recounts this history.

Brenda Sanders-Wise, executive director of the Tarrant County Black Historical and Genealogical Society, also stated that business intrusion had been a big concern in the Garden of Eden for decades. Brenda says they have dealt with this for most of their lives. 'Who knows what we've been inhaling all this time? We're still here, and there's no way we're leaving."

The Bottom

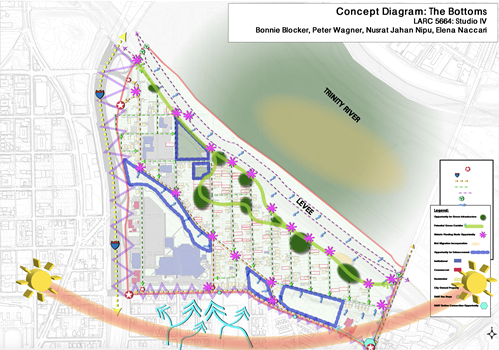

The Bottom is one of the closest neighborhoods to downtown, situated on "low-lying" terrain along the Trinity River. This was another stop on the tour, led by Dr. Diane Allen. The Bottom is a historic region next to one of the City's three former Freedman's towns, which was frequently flooded before the Trinity River Levee system's installation and has now been neglected over time. The Bottom is one of the communities in the riverside villages that are considering redevelopment. A once-thriving community has been steadily declining due to a shrinking residential population. This neighborhood today has 123 residents.

The Golden Gate Church Ministry was the center of the tour and one of the community's focal points. They have dedicated to providing community service to the neighborhood for many years. We spoke with the Pastor of the Golden Gate Ministry, who is also at the heart of the Bottom's revitalization and has been a part of the church ministry for almost 20 years. He mentioned they developed a master plan in 2015 to revitalize the remaining portion of the site, stabilizing the present residential area while developing guidelines to influence future development. Some of the designs may not be appropriate for the historical and cultural background, but they hope to maintain its significance.

Through visioning and planning exercises from numerous people, developers and organizations, The historically affluent neighborhood has begun to see a more exciting, sustainable, and inclusive future for its community. Dr. Joowon Im and her studio class visited the Bottom last year, and they met with representatives from the neighborhood association and the community development organization. The City of Dallas awarded the Bottom Neighborhood $500,000 for beautification.

They learned about the community's needs and the neighborhood's unparalleled potential at the meeting. The studio concentrated on the long-term repair and aesthetics of the Bottom neighborhood, which is hampered by deteriorated infrastructure and socioeconomic inequity. The beautification scheme was divided into three stages:

-

Work on landscape assessment to understand the environmental ecology and human settlements at the state and city level.

-

Analyze the site conditions and context of the Bottom at the neighborhood level and develop a master plan based on the analyses.

-

Design a selected study site in detail with a connection to the studied larger environmental systems.

They had recently examined these plans and discussed how they could implement it during a conversation with the Pastor of the Golden Gate Ministry. However, they are concerned about the amount of capital needed, but these plans will certainly help improve the neighborhood's overall outlook soon. The Pastor say the goals for the neighborhood include developing inexpensive single-family dwelling, encouraging economic development, facilitating community building, creating vehicular and pedestrian connections linking existing roadways, and so on. The Bottom is the best view of the city, and it is remarkable.

Mosier Valley

Mosier Valley was Texas's first all-black community. It was established a few years after the Civil War, primarily by former black slaves. There were few opportunities for them to integrate into the white towns of Hurst, Euless, and Bedford. Mosier Valley's social life revolved around church and school. The first schoolhouse in Mosier Valley was founded by previously enslaved individuals and now reduced to a historical marker in a Fort Worth park.

Benny Tucker, the longtime president of the Mosier Valley Community Association, assisted in the tour of the Mosier Valley at the Community Park. He gave a brief history of the community school that exited in this neighborhood. Mr. Tucker said the commemoration of Mosier Valley's rich history would not be complete until the city completes the neighborhood's four-acre park, which was officially dedicated in 2014.

Mosier Valley didn't have city services until the late 1990s, including water and sewer lines, streetlights, and garbage collection. Residents still believe City Hall often disregards their issues. "We're attempting to protect Mosier Valley's legacy now more than ever... nothing is more significant than the park, which would be such a great morale lift for the community because it belongs to them." Mr Tucker said.

Celebrations of Black culture continues to take place in the community, including a Juneteenth celebration in the park this past weekend. He encouraged the students' imaginations to explore what they could do for Mosier Valley Park and the community that survived.

Bear Creek

In the 1850s, settlers began to arrive in this part of western Dallas County and Following the Civil War, Freedmen from St. Louis MO relocated to Bear Creek. Families and friends who had previously been separated by slavery were reunited. Jim Green was the first African American to own property in the Bear Creek Community. He bought his acreage in 1878 to build his home with surrounding farmland that included livestock, a fishpond, and water wells.

Wanna Smith, a member of the CAPPA staff, is a descendant of Jim Green of Bear Creek, one of the 5th generations of a freed slave. Jim Green was a landowner who was exceedingly generous with his land. He gave land for the construction of churches, schools, and cemeteries. “My mother is now the proud owner of a couple properties purchased by her great, great, great, great-grandfather, Jim Green.” Wanna Smith is the Coordinator of Special Projects at the Institute of Urban Studies, one of CAPPA’s Research Centers. This was a wonderful opportunity to have Ms. Smith part of the tour at Bear Creek, and to get firsthand knowledge of its history and her personal experiences was remarkable.

Bonton Farms

The Bonton Farm is a neighborhood in South Dallas where poverty is widespread, and jobs are few. The Bonton endured racial injustice and systematic oppression and hindered the Bonton from taking advantage of opportunities available. Diabetes, stroke, and cancer were all more common in this area, and 48 percent of individuals were impoverished. Health and wellbeing, economic stability, safe and affordable housing, transportation, education, and access to fair credit were all denied to residents. Today, however, the town has begun to transform from within and thrives due to the Bonton farms.

The Bonton Farms promotes development in reclaiming unoccupied land for the sake of employment creation, revenue generation, and the promotion of healthy diets and behaviors. They've grown from a little garden to two fully operational farms, a Farmer's Market, a Café, and a Coffee House. In the Bonton neighborhood, they continue to raise organic food and hope for a better tomorrow. They are also working to remove more obstacles to gain access to all basic human necessities. "We assist our neighbors in redefining the norm in this community so that they can have a fighting shot at life." Their mission statement is to "transform lives by disrupting systems of inequity, laying a foundation where change yields health, wholeness, and opportunity as the norm."

Bonton Farms has attracted a great deal of positive attention for breaking the cycle of poverty. They're standing up to the short-sighted solutions and complacency that have afflicted the neighborhood for years. "The neighborhood's goal should change from within, driven by the people, and wealth coming back into the community."

The Undertaking

The students will be divided into smaller groups this summer to analyze how the six DFW cities deal with land use, zoning regulations, preservation rules, and industrial and housing development. Some students will also revisit the Freedmen's town and eventually create a "digital essay" video to help with the "Design Playbook" project.

In the following weeks, students will travel to Elm Thicket and Joppa, a South Dallas neighborhood that has received national attention for the impact of illicit industrial pollution on its residents. The “Joppa Team” has collaborated with members of the community and groups, such as the South-Central Civic League in Joppa, to ensure that their findings reflect the views of locals.

As historians, landscape architects, student designers, and community leaders, there is so much work needed to preserve these communities. The Hope is that this undertaking could improve the quality of life by increasing green space, policy change, zoning laws, preventing flooding, and more.

- Written by Onome Aganbi